3-Bullet Summary

You’ll benefit more from reading the article the whole way through. But, if you’re pressed for time, here’s a condensed version of The 5 Best Places to Find Academic Sources for Free:

- Academic sources are the best possible proof you can use to support your arguments.

- Academic sources take many forms, ranging from academic books to scholarly journal articles, but all meet the same criteria: professionally written, peer-reviewed, objective, up-to-date and presentable.

- The 5 best places to find academic sources for free are Google Scholar, institutional resources, academic reference lists, Google Scholar’s ‘Cited by’ database, and Google Books.

Introduction

First-class essays are dictated by many factors. However, there’s one factor that you can take action on today to stand out to your examiners.

The quality of the sources you cite to back yourself up.

The reason for this factor’s importance is quite simple. Imagine that you’re trying to prove to someone that you’re a great cake baker. Out of these three options, which would you do to prove yourself?

- Say that you’re a great cake baker without baking a cake.

- Bake a cake that isn’t great.

- Bake a cake that meets the criteria for greatness — tasty, aesthetic, etc.

Obviously, you’d pick the third option; you want to physically show someone that your point (“I’m a great cake baker”) is grounded in the most undeniable, trustworthy evidence possible (“Here’s a delicious cake”).

Essay paragraphs work in the exact same way. Just like how you proved you’re a great cake baker through a widely accepted example of cake-baking skills (baking a cake), the points and arguments you establish in response to an essay question need the same quality of support.

This is where academic sources come into play.

What are Academic Sources?

Academic sources are the proof that your points and arguments are grounded in sound evidence — they’re the great cake that proves someone is a great cake baker.

There are several criteria that academic sources hit:

- Written by academics with PhD qualifications — academic sources are produced by experts with qualifications to back themselves up. You’ll know they’re an expert in their field if they have ‘Dr.’ or ‘Prof.’ before their name. They’ll also typically belong to an institution, like a university or college.

- Peer-reviewed — the authors of academic sources often have their work fact-checked and debated by other academic researchers.

- Objective and scientific — the writing in an academic source isn’t one-sided, opinionated or extreme. It functions to test a hypothesis/research question and prove it wrong or right with evidence.

- Up-to-date — the best scholarly literature is contemporary. This means that articles published over the last 20 years are more valuable than those published before then.

- Presentable — academic sources will have a bibliography/reference list dedicated to acknowledging all the other academic sources they’ve used. They won’t be littered with ads and sponsorships, nor look like they were published unprofessionally. For instance, you won’t see spelling errors or things out of alignment.

Types of Academic Source

Academic sources can take many forms. However, instead of using a huge variety of them, you’ll typically use a few different types.

So, to save you from searching for academic sources that you’ll only ever use a few times, here are the most common academic sources that you’ll use on your academic journey:

- Academic journals — collections of professionally published articles that are typically peer-reviewed. These will be your bread and butter, regardless of subject area.

- Academic books — texts written by professionals within a specific field. These books are different from normal books because they’ll meet pretty much every criteria of an academic source.

- Conference proceedings — written versions of works presented at academic conferences. These conferences are basically big gatherings of professional researchers nerding out on their subjects. These proceedings are typically published in academic journals.

- Grey literature — governments and charities may provide access to reports, working papers (reports that haven’t been fully published), unpublished reports and white papers (documents setting out proposals for future policies and actions).

- Theses and dissertations — academic research projects published by undergraduates and master’s students.

Where to Find the Best Academic Sources

Now that we know what an academic source is and the most common forms they take, we’re going to discover where they’re hiding.

The following tools are listed in descending order of importance. Number one is therefore the best way to search for academic sources. Nonetheless, this does not mean the other tools are unimportant; you should use all of them for your projects.

For sake of demonstration, we’ll search for academic sources related to ‘sleep quality’. This will teach us about how to use these tools for research projects.

1. Google Scholar

If you master Google Scholar, you will never have major problems when it comes to researching for assignments, as this tool is the gold standard of academic search engines.

Its interface is practically the same as normal Google’s, which is intuitive to almost everyone. You simply enter your search term, hit search and you’ll soon be overwhelmed with academic sources.

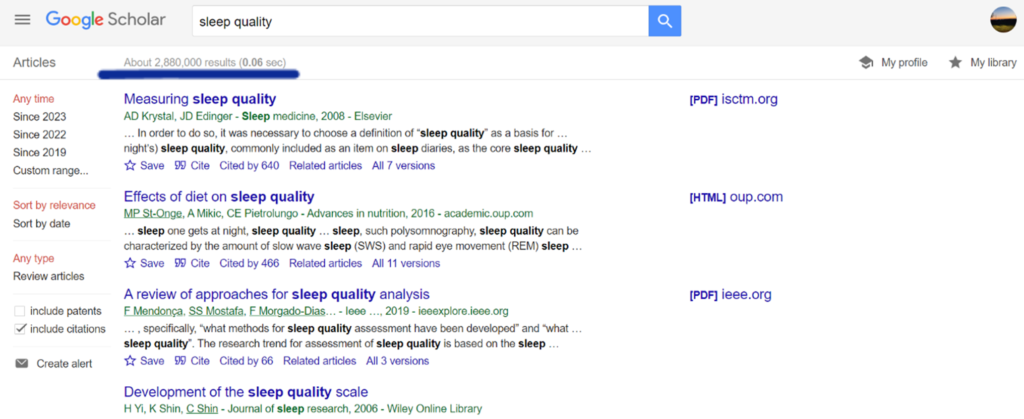

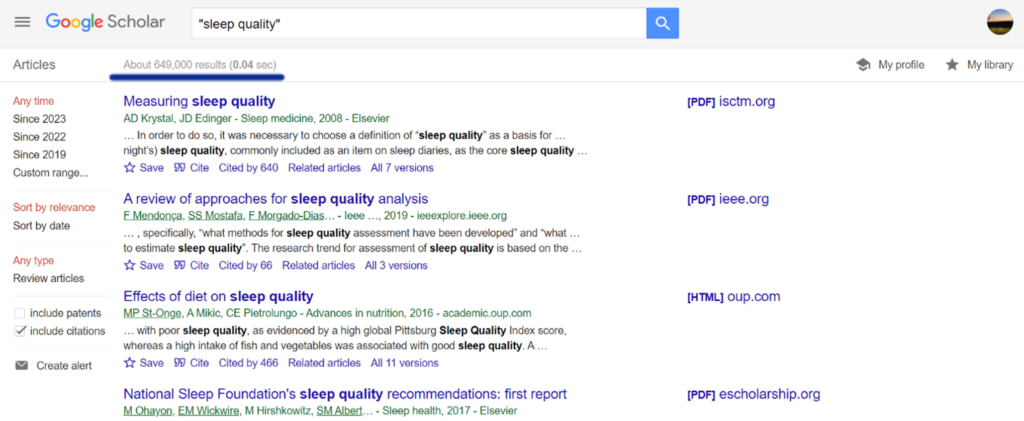

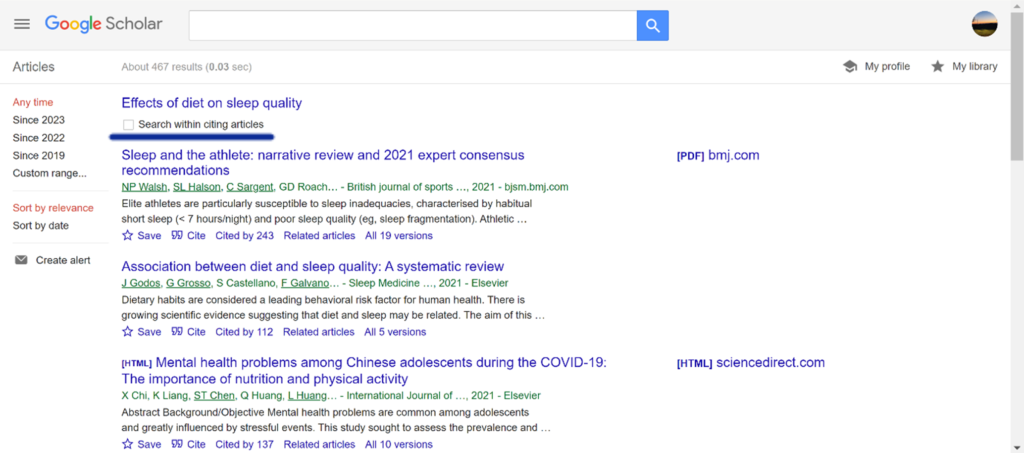

The more vague you are with the terms you enter, the more results you’ll get. Because ‘sleep quality’ is researched and written about in so many contexts (things improving sleep quality, things having negative impacts on sleep quality, changes in sleep quality according to time and demographic, etc.), we get a huge amount of results — over 2.8 million.

Moreover, because we haven’t used any advanced search features or Boolean operators, our search is incredibly broad. For instance, by not using the speech marks (“”) Boolean operator, which means ‘exact phrase’, Google Scholar is searching for ‘sleep quality’ as well as ‘sleep’ and ‘quality’ on their own. If we use this operator, we get a more drilled-down search into the topic of sleep quality. This is illustrated by the reduction in search results.

Although a full Google Scholar tutorial that digs into advanced search features, Boolean operators, and all the other powerful functions it performs is beyond the scope of this article, the Strong Students library contains The Ultimate Guide to Google Scholar, which will literally take you from a beginner to confident in navigating the search engine, step-by-step.

2. Institutional Resources

There are two main types of institutional resource, which, if you have access to, you should use for all your assignments: library websites and assigned reading lists.

Library Websites

If you go to a university or college, chances are that you’ll also have access to a library.

This library will probably physically exist, meaning you can visit it organically and pick up books by hand. But, there’s a good chance that the resources within the university or college are available online through a digital library. If so, then you literally have free access to academic resources 24/7 and don’t have to waste time traversing Floor 2B.1: Row 6.14783D1 for one book.

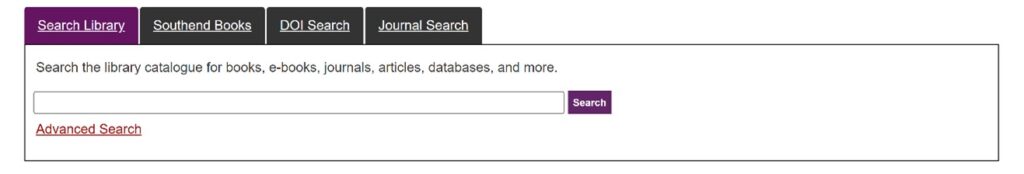

Digital libraries will function in a very similar way to Google Scholar. Using the University of Essex’s library as an example, you have a simple search bar that you can enter your keywords into.

This search bar, if left unmodified by advanced search features, will return results that include any variation of the keywords entered, exactly like Google Scholar does. The screenshot below demonstrates this, as although our search term was ‘sleep quality’, the keyword ‘sleep’ is highlighted. The search engine thus deemed sources as being relevant for including the words within ‘sleep quality’ instead of the whole phrase.

Depending on your institution, the online library may work differently. Your university may not permit Booleans, for example, and require you to use built-in advanced search tools if you want to refine your search.

One last point is that certain academic sources may be owned by the institution but not digitised. Therefore, although a resource may appear in the online database, it may only be available for in-person rent. If so, use the online library to pinpoint exactly where the resource is in the physical library, as well as any others you think would be helpful for your assignment, and gather every academic source you need in one trip.

Assigned Reading Lists

During the term at university/college, you’ll be assigned a whole load of essential readings. These are academic sources that your lecturers and teachers will require you to read before your lectures.

Alongside essential reedings, you may also be pointed towards supplementary readings (sometimes called additional, recommended or further readings), which are academic sources related to the essential readings’ content.

Essential and supplementary readings are collated in assigned reading lists that your institution provides access to. These lists will differ per institution but are always really valuable. They’re like mini libraries of high-quality academic sources that the people marking your assignments want you to cite.

Furthermore, they’ll often be broken down into different topics that map to different lectures conducted during the term. This means that they’re already neatly categorised for you; if you want academic sources related to a specific topic, just go to the section of the assigned reading list corresponding to the week you covered that topic and pick out the sources you need.

3. Reference Lists From Other Academic Sources

This is the most underrated way to find scholarly articles by far.

Say you’re using Google Scholar and find a journal article that is directly relevant to your assignment.

When you click the link to be directed to the website, you’ll see information about the authors and the journal.

If you scroll down a tad, you’ll see the abstract, which is a concise summary you can use to judge how helpful the article will be for your purposes.

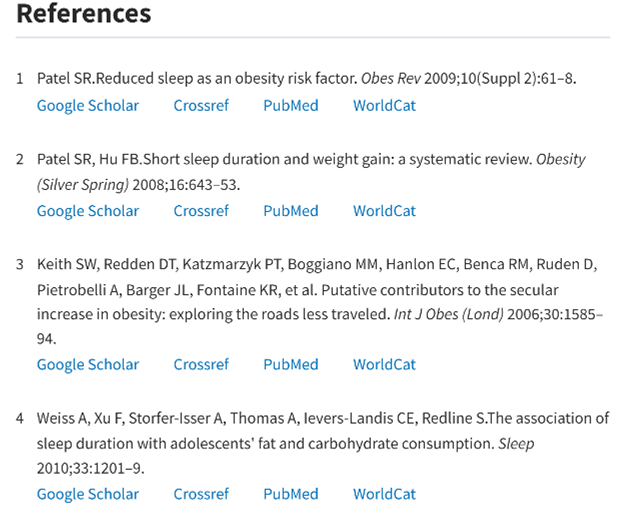

A keen eye will also see that there is a ‘References’ hyperlink detailed in the ‘Article Contents’ sidebar.

If you click on this hyperlink, you’ll go to the reference list at the bottom of the page. Here, there are literally tens of scholarly sources at your disposal.

Although not every journal will be setup in this way, most of them will. Even if the journal article you find doesn’t have hyperlinks to the reference list in a tidy sidebar, it 100% will have a reference list at the end. If this is the case, scroll down to the end of the article and find the reference list that way.

This strategy, which is known as double-dipping, isn’t just confined to journal articles. Recall that for an academic source to be considered as such, it must be presentable. One of the features of a presentable article is a reference list or bibliography. Therefore, all the academic books, conference proceedings and dissertations that you find in addition to journal articles will enable you to use not only the original source, but also a host of sources stemming from them.

Be Aware of the Original Article’s Date

Before moving on, a quick word of caution. Double dipping is most effective if the original source is relatively new. If the source was published 20 years ago, and is therefore pretty old, then all the academic sources cited will automatically be even older. This is because referencing future academic sources is impossible (unless you’re a time traveller). Academics can only work with what they’ve got at the time, which will inevitably be older than the work they’re producing.

So, make sure that you milk the best academic sources you find dry, but only continue milking if the source is young and fresh, as this increases the chances that the other sources cited within it will also be relevant.

4. Google Scholar’s ‘Cited by’ Database

“Wait, wasn’t Google Scholar number one?” you may be thinking. And you’d be correct; Google Scholar tops this list — for its search function.

However, it makes number four because it has a second mechanism that you can exploit to extract high-quality academic sources: the ‘Cited by’ database.

Extracting Academic Sources from the ‘Cited by’ Database

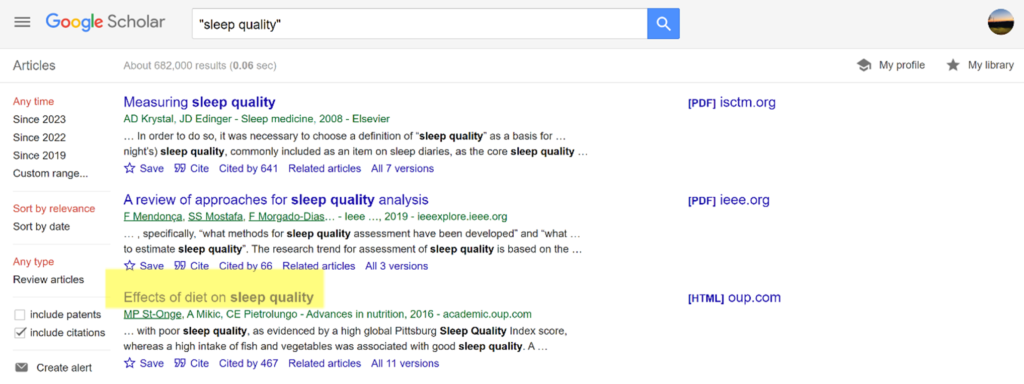

Let’s revisit that really good article from earlier. If you look just below it, there’s a hyperlink that says ‘Cited by’.

If you click this link, you’ll be taken to all the published digital sources that have cited this article.

The beautiful thing about this is that all these sources are guaranteed to be more contemporary than the original source. This is because they’ve cited this article, meaning they’ve drawn on it to inspire their work. This contrasts the potential weakness of academic literature extracted from another source’s reference list, which is by default older than the original.

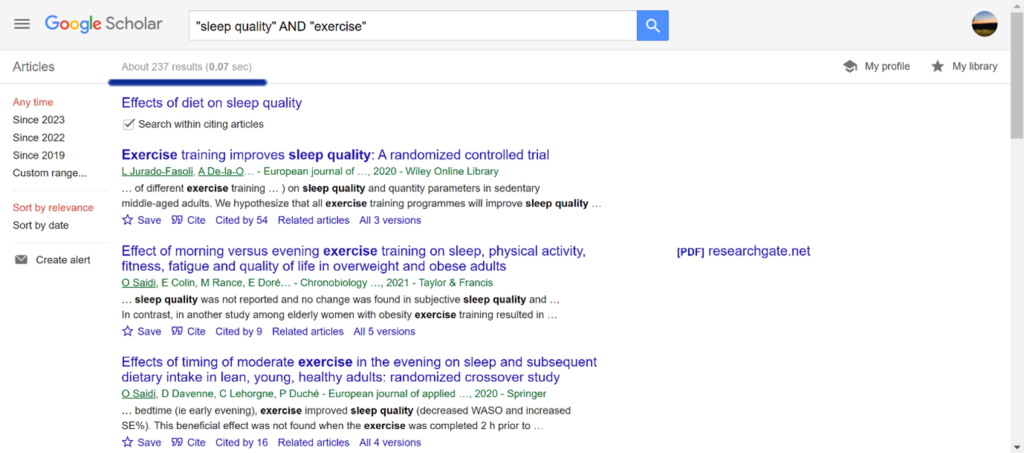

Within the ‘Cited by’ database of an academic source, a tick box appears that says ‘Search within citing articles’.

If you tick this box, then you can utilise the search bar to only search for articles within the ‘Cited by’ database. All the same advanced search features and Boolean operators apply from the original Google Scholar search bar. In the example below, you’ll see that the utilisation of Boolean operators narrows the search down within a highly relevant pool of academic sources.

This feature is honestly brilliant. You can find up-to-date literature and apply your knowledge of the Google Scholar search bar, allowing you to find some real gems for your assignments.

As a final note, you may have noticed that sources in an article’s ‘Cited by’ database also have ‘Cited by’ databases. This means that you can really go deep into the rabbit hole of scholarly literature from just one good source, and the further you go the more recent the articles get.

5. Google Books

I hope you’re beginning to realise that Google is, in gamer terms, overpowered.

Google Books is another Google tool that you should add to your academic research arsenal and wraps up this list.

It’s very similar to Google Scholar, as it contains a search bar that can be refined with Boolean operators. But, Google Books only returns academic books.

The reason Google Books ranks low on this list is because you don’t get the ability to preview — let alone fully access — all the books displayed by the search engine. Despite this, some books permit you to preview them. Google will signal which books can be previewed via a peeled-over page icon on the book’s thumbnail, as well as a ‘Preview’ button.

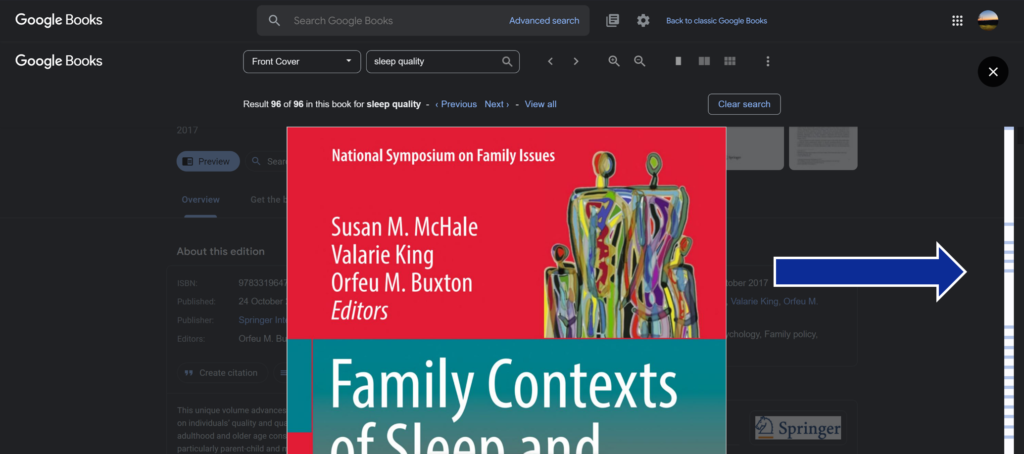

If you preview a book, you’ll be taken to the book’s front cover page. At this point, the magic of Google Books commences.

Google Books’ Results Bar

The first trick up Google Books’ sleeve is the bar to the right. This bar is laced with little blue rectangles.

These little blue rectangles actually pertain to pages within the book that contain your original search terms. If you hover over the blue rectangles, you’ll see a quote containing your search terms and the relevant page number. Upon clicking a blue rectangle, it’ll go yellow and you’ll be taken to the relevant pages containing the search terms.

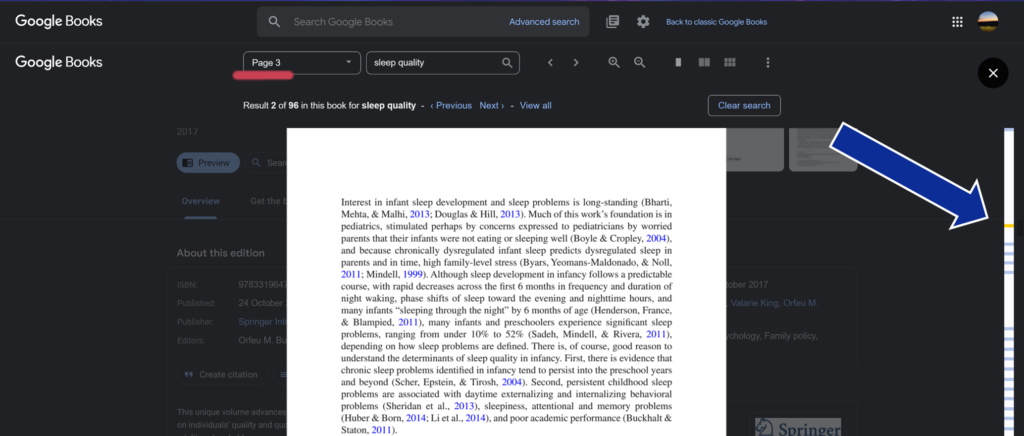

If you then hit ‘Next >’, you’ll be taken to the next page containing your search terms.

Alternatively, clicking ‘View all’ provides a birds-eye view of your search terms throughout the entire book.

Google Books’ Search Bar

The second amazing feature of Google Books is the search bar. When you preview a book, you’ll notice a box containing your search term.

If you modify the search term in this box, then Google will scan the book for it and provide a host of new pages. This is great, because if you want to then see whether an already good book has more relevant data for your assignments, you can do so without having to go back to the dashboard.

Using Libraries to Supplement Google Books

If you find a book that ticks all the boxes for your assignment but you want full access to it, then enter the book’s title into your institution’s library website.

There’s a good chance one of the two following things happen:

- Your institution will have a digital version of the book that you can access upon signing in (yay).

- Your institution will have a physical version of the book that you can access by going to the library in person (yay but less so than before).

In the case of the book being used for demonstration purposes, my university had a digital copy!

Final Thoughts: The 5 Best Places to Find Academic Sources for Free

One of the most daunting things about writing for academics like lecturers is that you can no longer rely on good old Google and Wikipedia for your assignments. You’re expected to engage with professionals in the subject you’re studying. Hence, you can’t (unfortunately) cite Bill Nye for your science projects.

However, this guide has given you five tools that you can use for the rest of your academic career. They’re all time-tested and widely recognised sources of academic literature that will guide you towards first-class essays in little time and at no cost.

So, cut out the noise online and get really good at navigating and utilising these five resources. The more time you spend learning and extracting academic sources from them, the better your grades will get. Our promise.